by Angela Anderson and Ana Hoffner ex-Prvulovic*

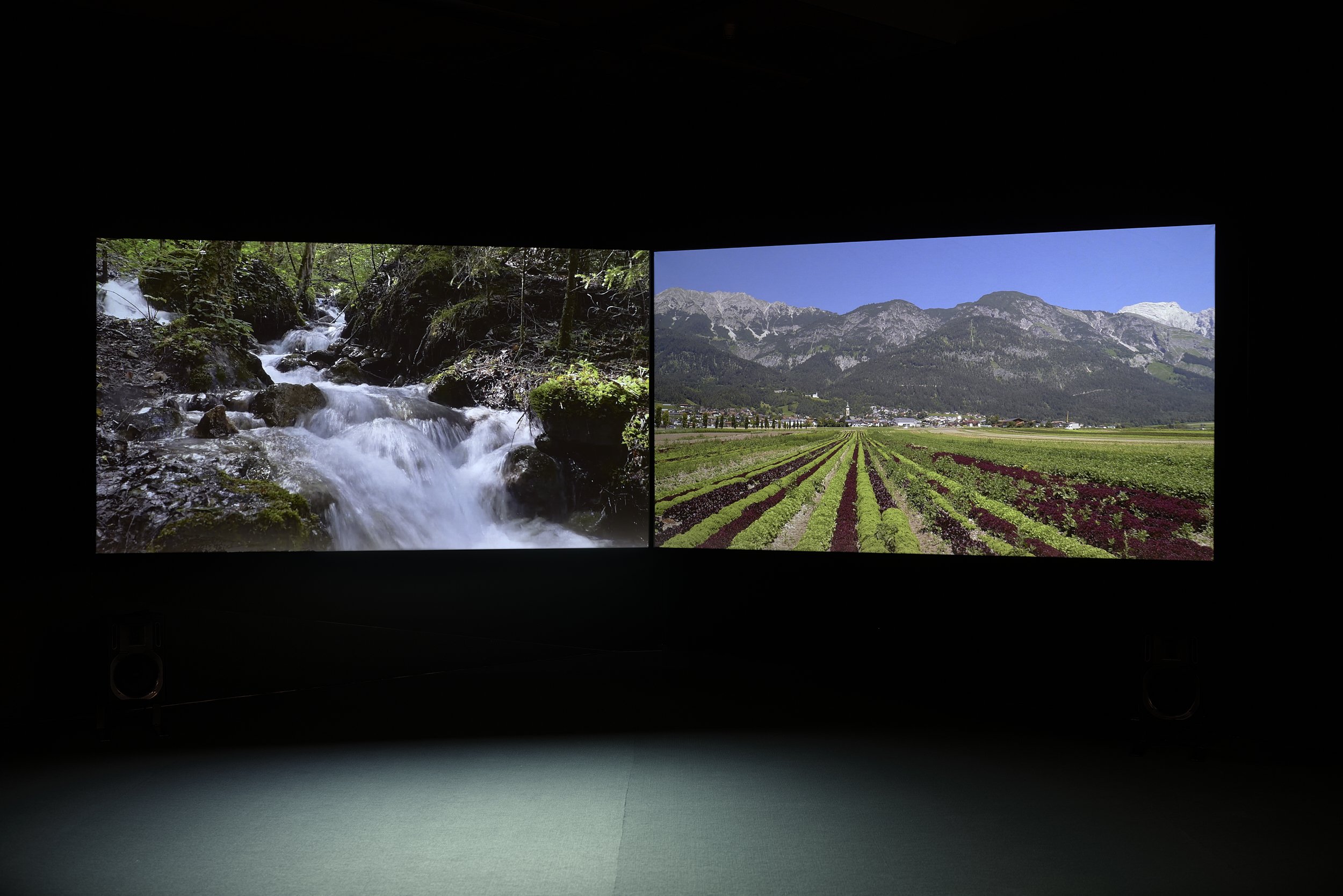

Two-channel video installation, HD color, stereo sound, 42:25 min.

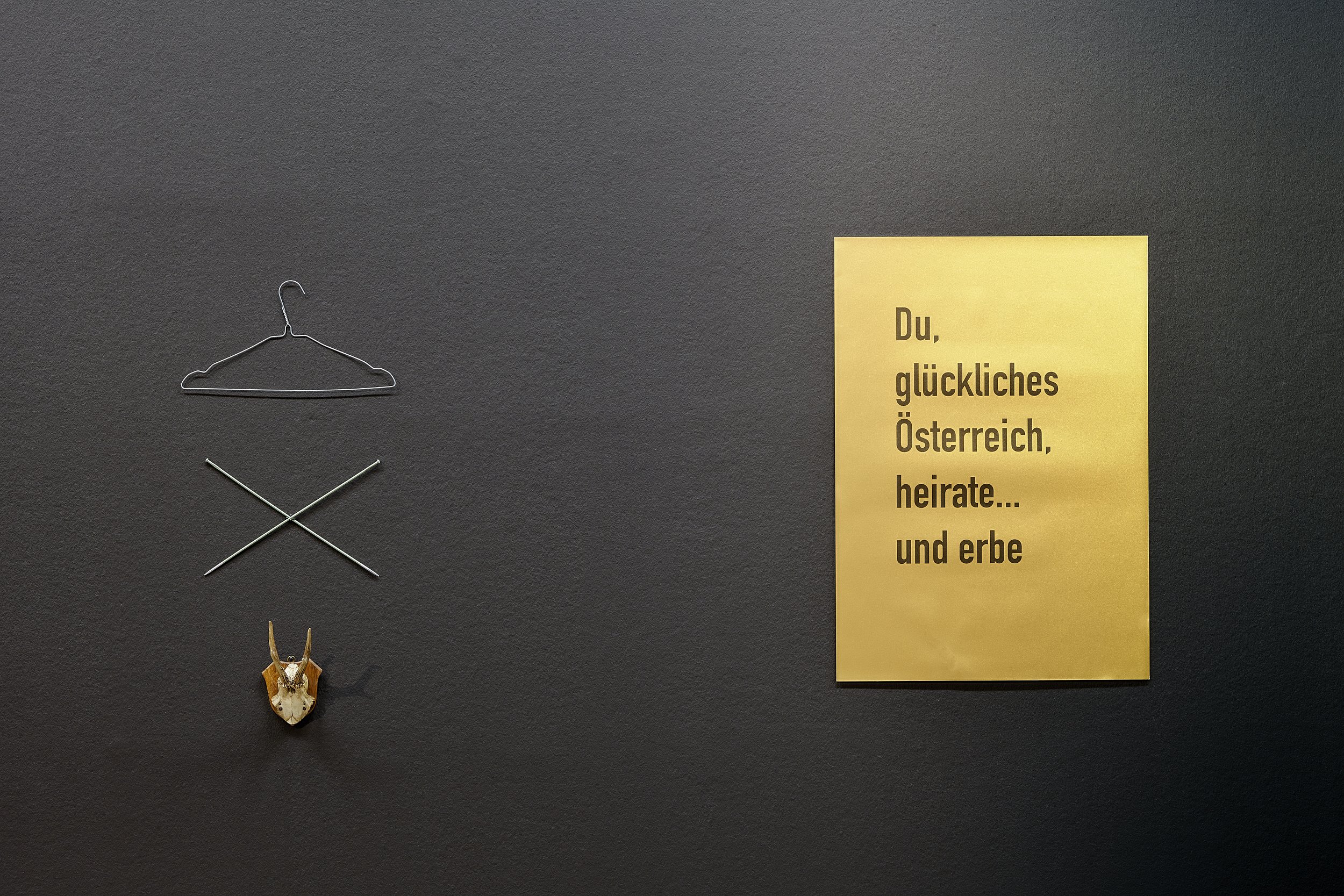

Vegetable boxes, clothes hanger, knitting needles, antler, NFC bracelets, clay relief, T-shirts, stones, wild carrots, clay objects, plant lamp.

Vinyl foil, 250 x 121.6 cm

Print, 84.1 x 59.4 cm

Pigment prints, framed, two 30 x 40 cm, two 30 x 43.3 cm

Pigment prints, unframed, four 20 x 30 cm

C-print, unframed, 50 x 71.4 cm

C-print, unframed, 80 x 59.3 cm

C-print, unframed, 59.3 x 41.5 cm

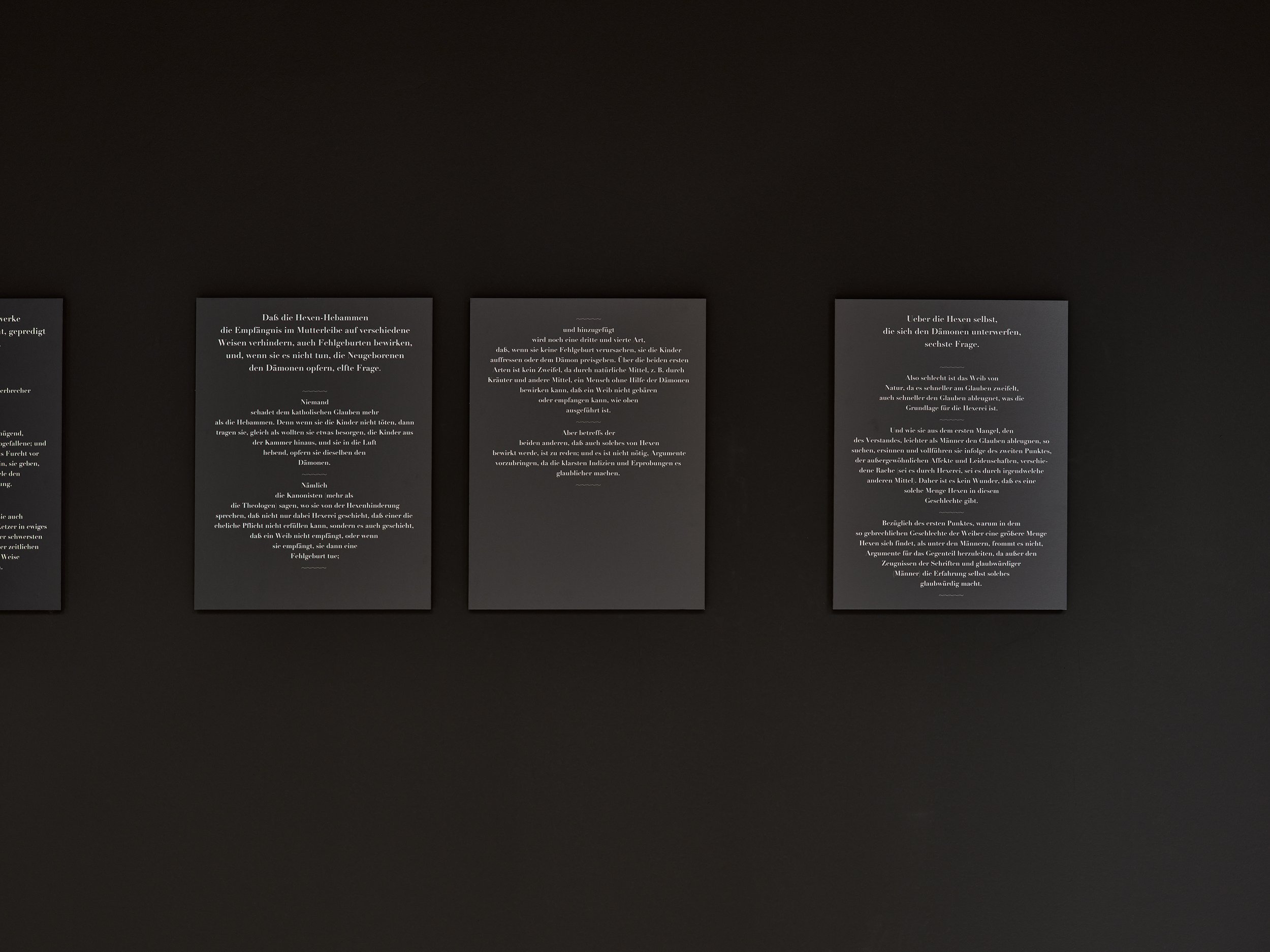

Pigment prints, laminated on MDF, six 30 x 40 cm

Public intervention

47°16'59.5"N 11°23'52.1"E

“In memory of the women who were tortured and murdered as witches between 1450 and 1750.”

Commissioned by

TAXISPALAIS Kunsthalle Tirol

for WITCHES

Following the traces of the historical figure of the witch in the Austrian province Tirol, Hexenküche (The witch rarely appears in the history of the proletariat) examines the emergence of neo-feudalist power relations caused by the contemporary and ongoing land expropriation of the post-socialist European peasantry and capitalist land reforms from the perspective of feminist Marxist theory. Working with a textual layer excerpted from Silvia Federici’s Caliban and the Witch, the work brings the contemporary situation of so called “Erntehelfer” or “harvest helpers” (migrant harvest laborers) in Tirol together with the historical moment of the witch hunt, which according to Federici enabled the establishment of capitalist modes of production in the transition from feudalism to capitalism. While the correlation of the figure of the witch with the struggles of peasant women is seldom made, the stigmatization and marginalization of dispossessed workers in the agricultural sector through the mystification of harvest labor as poorly paid ‘help’ is ubiquitous, thus obscuring their exploitation along the structurally gendered categories of reproductive labor.

The installation opens the field of migrant harvest labor as a site of capitalist reproduction to its broader biopolitical function in the creation of race, gender and nation. It juxtaposes the feminist strugglesaround abortion and women’s rights, and the feminist movement’s reappropriation of the figure of the witch, with the reproductive futurity of present-day land owners, who use harvest workers for the reproduction of the white Austrian family and traditions. The romaticized ideals of the heteronormative family and the authority of the catholic church (which is fundamental to the life of the region) are disturbed by the presence of feminist and migrant voices (Sonia Melo from Sezonieri - campaign for the rights of agricultural workers in Austria, Gerti Eder from the AFLZ – Autonomous Women and Lesbian Center in Innsbruck, Monika Jarosch from AEP (Emancipation and Partnership Working Group in Innsbruck) and Ingrid Strobl, co-founder of AUF (Independent Women Action in Wien) and editor of the feminist magazine EMMA (1979-1986). Close-ups and the long-shots of the Tyrolean landscape and plant environments serve as potential carriers of a different way of living together. The work thus callsfor a movement that would question capitalist reproductive labor from both the perspective of the body and the land.